Increased anxiety may often be triggered from past experience. The approach of Hurricane Sandy toward the New Jersey coast (home during my youth), the projection of it morphing into a Superstorm, and the prospect of the storm surge hitting on top of an astronomical high tide raised my anxiety higher. My New Jersey family includes my father, my brother and his wife, and my two nephews and their families. What their communities faced was similar to us in 1989, and those deeply ingrained memories from Hurricane Hugo triggered more angst, early morning awakenings, and distraction. Like others, I was riveted to news coverage, with correspondents broadcasting from familiar Jersey beaches.

As the storm made landfall and the devastating results came to light, my mind continued to spin ideas growing into a plan: make the trip north. Not fly, but drive, and carry goods. In the immediate aftermath, all Raynors were without power, including my father, at age 93 residing in a retirement community. My brother and his wife evacuated their condominium in the beachfront community of Monmouth Beach, and their presence with my ninety-three year old father kept me from precipitously heading north. I continued daily to watch the coverage of the aftermath on the news and the internet, and to formulate my plan.

I’ve traveled into disaster zones before. Besides living in one after Hugo, I made the trip to Durham, North Carolina after Hurricane Fran. This time I would not be taking my chainsaw with me, but instead a cooler full of lasagne and other goodies for the Raynor family. Watching the coverage of gasoline shortages, I brought a five gallon gas can for emergency use. The state had just implemented rationing, but there were no lines at the service centers along the NJ Turnpike. Remarkably, I only saw one tree down along the Turnpike, and none on the leg across the state toward the coast. Only within miles of the coast did the familiar sight of downed trees become evident.

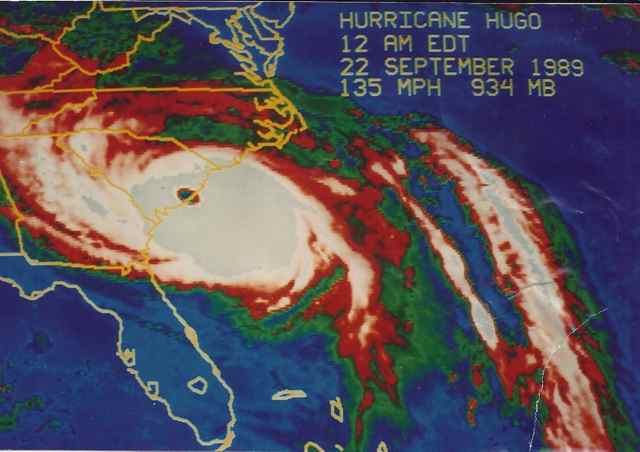

Noticing the trees helped me recall the effects of a category 4 hurricane on the coast and landscape. The objective view was that the Lowcountry of South Carolina was “fortunate” since the worst of Hurricane Hugo made landfall in a rural area north of Charleston, much of it unpopulated due to the federal holdings of Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, and Francis Marion National Forest. We learned where the most dangerous spot of a hurricane resides, the northeast quadrant eyewall. Since the “sweet spot” of Hurricane Hugo came ashore over Bull Island and Bulls Bay, and my community of Romain Retreat, the education was extreme. What do sustained winds of over 135mph do to trees and houses? How high does the storm surge rise, and how far does the force of that water create havoc? Coming home to Awendaw after our evacuation to Columbia, we attempted to drive the back way through Francis Marion Forest, since we were not sure I-26 would be open. Having traveled halfway, the road went from 2 to 1 lane, narrowed due to downed trees sawed by locals. We were confident about getting through, carrying a couple of chain saws and sporting a winch on one of our vehicles. We then went from 1 lane to none, and I got out to survey, climbing over several large pines laid across the road. I picked one with a tilt to climb and get some perspective. The view was impressive – as far as I could see were massive pines laid across the road. Our tools were inconsequential to the forest covering the road (we backtracked and found our way home via I-26 and Hwy17). A later calculation was made: if all the Francis Marion Forest trees downed by Hurricane Hugo were sawn into boards 1 inch thick by 12 inches wide, putting those boards end to end would wrap around the equator of the earth seven times! It was way beyond our imaginations, and the absolute worst thought was the possibility upon our arrival home that our neighbors who stayed in their houses might have perished.

We were fortunate that our friends survived, though their recovery from a night of terror and facing the violence of the storm was not easy. Walking back into our neighborhood (roads not open) was surreal, since no landmarks remained. The forest was leveled, as were many homes. The community appeared as if it had experienced the effects of a nuclear explosion. Shell-shocked neighbors seen on the way numbingly stated that Romain Retreat was “all gone”. So after climbing over trees to get to my house, I joyfully found it amazingly had survived. There was a toll, and initially I saw that 40% of my metal roofing was blown away, and a number of large trees lay on the house. (We learned later that our community had the unfortunate designation of recording the highest storm tide on the east coast in the twentieth century – within a hair of 20 feet.) I was fortunate to get a crew with a small bulldozer and chainsaws to remove the trees from the house and my driveway in the following week so I could put on a temporary roof. “Bear”, the leader of this crew, was also a Vietnam Veteran. Like other vets from that war, the devastated landscape, and the helicopters passing regularly overhead, contributed to their re-experiencing of war trauma. He and others noted one difference – the absence of the aromas of napalm and death.

On my second day in Monmouth County in New Jersey, my brother Doug took my father and I into his home community of Monmouth Beach (National Guard checkpoints – residents only) to see the damage. (He continued after a week with no power). Telltale signs marked the streets of areas never before flooded (in memory) – debris piles head high along the road, contractor vehicles, front end loaders, and dump trucks. Doug’s home was on the third floor of a condominium tower with a view to the South Shrewsbury River. Boats from the marina had rammed through a barrier fence and littered the lawn of the condo.  The ocean had joined with the river in the storm surge, and on the far bank yachts were strewn chaotically. It looked all too familiar. Sandy was the storm that the Jersey Coast feared but never thought would occur. We walked down to the beach, and fortunately the stairs were still intact to climb over the tall seawall that runs the length of Monmouth Beach.

The ocean had joined with the river in the storm surge, and on the far bank yachts were strewn chaotically. It looked all too familiar. Sandy was the storm that the Jersey Coast feared but never thought would occur. We walked down to the beach, and fortunately the stairs were still intact to climb over the tall seawall that runs the length of Monmouth Beach. These beaches are regularly renourished, and we found little beach left on the other side of the wall. A fossil jumped out at me on the strand.

These beaches are regularly renourished, and we found little beach left on the other side of the wall. A fossil jumped out at me on the strand.

It was a beautiful clear day with a placid ocean – the proverbial calm before the storm. As had been forecast, a nor’easter was coming up the coast to impact again this damaged and vulnerable area on the following day. I was staying with my father in his retirement community, Seabrook, located in Tinton Falls about 6 miles inland from Asbury Park. I made a trip in the early morning to a local beach, Ocean Grove, and found there no checkpoints or barriers. It was blowing a full gale, and the beach provided a sandblasting. Much of the boardwalk remained, a usual venue for my runs in NJ, though the storm had left it in waves. The fishing pier was gone. Unlike Monmouth Beach, there were no debris piles, and a resident out for a walk informed me that they only received an inch of seawater in the streets. This beachfront community has made major efforts to protect its dunes, and I noticed that many were intact.

There appeared to be a glimmer of improvement in the forecast – the storm would pass a little further to the east, meaning reduced storm surge. Yet snowfall was creeping into the forecast, and predicted in Monmouth County. It started at noon, and continued into nightfall. Rising early the following morning, I ventured out for a walk. The snow was wet and heavy, and a tree’s branches sagged on to my truck. Circling the Seabrook community, I found a depth of about 8 inches of snow. It was a winter wonderland, and a deceptively beautiful one.

Upon my return inside, the power was now off, returning the retirement community of 1000 people to the state experienced immediately after Sandy – no power or heat. It was a cruel blow, and suffered by a number of people in the hard-hit coastal counties of Monmouth and Ocean. The outage would last another forty long hours.Memories of past nor’easters returned to my consciousness in the following days. I recalled back in the early 1970’s sitting in a beachfront cottage of a friend’s at Nags Head in a storm, feeling wind gusts finding their way through the shingled exterior and shaking the building. It was the perfect atmosphere for reading David Stick’s Graveyard of the Atlantic. I learned that ships sailing south would run the gauntlet between the northward running Gulf Stream and the treacherous shoals and breakers of the Outer Banks, and the fate of many was to become wrecks on the coast.

One of the great adventures from my college years was a camping trip to the Outer Banks in February of 1973. We planned to camp in the dunes of Hatteras Island, though on the way to the coast we heard a radio report of inches of snow in Charleston S.C. It sounded ludicrous, and we didn’t believe it. We arrived on Hatteras, and when we walked out on a path through the dunes at night we realized that the gale force winds would blow our tent away. We sought shelter at Nags Head, and chose to sleep on the downwind side of the porch at our friend’s beachfront cottage. It was a wild night, and when we awoke after sunrise found snow drifting around our sleeping bags. The storm continued to rage, and we heard reports of several cottages washing into the ocean via the storm surf. It was time to retreat, and we began our drive back to Chapel HIll. What we did not know was that this storm had hit eastern North Carolina with the biggest snowstorm in memory. Our 6 hour standard trip stretched out to 12, and somehow but once again my old reliable ’65 Chevrolet Impala “The Green Pig” got us home safely.

I was drawn to the North Carolina coast to live after college, and found a home for a while in Wrightsville Beach, NC. My passion for sailing continued to grow, and I pushed myself and boat in larger waves and higher winds. I recalled seeking out winter gales for sailing in the protected waters of the Banks Channel behind Wrightsville Beach, and on one particular day my friend Alan Held and I took on the gale force winds in our Lasers. We put in triple reefs to reduce sail, but still had plenty of power and an unforgettable ride. (See photo on Sailing page).

I came across an account recently of the renowned sailor Joshua Slocum, and a trading voyage he made from New York to Montevideo. He set out as master of the ship Aquidneck carrying a cargo of case oil. But this happened to be his “honeymoon voyage” with his second wife, just married for 6 days, and accompanied by two sons (teenaged and 4 years old). The sailing conditions were severe on this February day in 1886, for the Arctic air had frozen the Hudson River, ships were torn from their moorings, and the winds were forty knots. For a sailor of Slocum’s experience the following winds would have seemed to be a benefit in voyaging south. However the winds would increase in the Atlantic to eighty to ninety knots – hurricane strength. Following waves began to crash over them, and the Aquidneck took on water,. For 36 hours straight Slocum and crew manned the helm and pumped constantly, battling against the strong possibility of sinking.

I’m sure my father growing up in Westhampton, Long Island, NY, had experienced his share of nor’easters. He also had barely dodged the Great Hurricane of 1938, nicknamed the Long Island Express. He had returned to school in Syracuse just days before the hurricane without warning roared across Long Island. He had to call the police department in Westhampton to go check on his parents to make sure they were safe, since over 20 people were killed in that town – over 500 deaths overall for the storm along the coast. He did not miss Sandy, but his location about six miles away from the coast was a safe one.

Like many people, I have been fascinated by storms for years, through first person experience, watching coverage of storms on TV, and reading about historic storms from the comfort of an armchair. I have learned that nor’easters draw on the energies from the cold Arctic air masses, and the warm moist air over the Gulf Stream, and like hurricanes are cyclonic lows that also can have eyes. I have read about many historic storms (Long Island Express 1938, Galveston 1900, the Perfect Storm), and the many storms impacting the South Carolina Lowcountry. I have visited a remarkable structure, a brick storm tower built after the Great Gale of 1822 that drowned scores of slaves on the Santee Delta. I can see daily signs of Hurricane Hugo on my property – damaged but surviving trees. I have also watched the regeneration of the maritime forest on Bull Island. And I wonder about the rebuilding of the New Jersey coast. I was struck by Governor Chris Christie describing the need for doing it smartly, and over a period of months and years. During the peak of Sandy’s surge in Manhattan, The Weather Channel’s Jim Cantore used his “podium” at the Battery to project toward the redevelopment, imploring leaders to project not just to 100 but 500 years. This will be a difficult view for the public and the political bodies to embrace, for it will mean some retreat from the coast. Hopefully the storm education provided by Hurricane Sandy will mean important lessons learned and utilized in the future.

Thanks for this Bob, well done. I was so relieved to learn that your family was safe… How many times has New Orleans been beaten to the dirt only to be rebuilt and will we ever learn?…c

But the will to retreat from the coast – can you imagine that happening? We are so fortunate that we have barriers that can migrate from Capers to Hobcaw Barony in our wonderful section of the coast. So folks can visit these places but not reside in the dynamic margins.

Time for me to visit the edge this weekend.

Thanks for sharing Bob – incredible story and pictures and how you and the family were affected by 2 major events. So glad everyone is safe

Pam

By the way, we remember the “Hugo” snow that occurred in December of 1989 – part of the memories of that singular fall. And there will always be the “Sandy snow” – the followup nor’easter the week after Sandy.

Very nice post! And many thanks for coming to make sure we were all ok and sharing some SC love!

Did you ever figure out what the fossil is from?

Not coming to NJ after Sandy did not seem an option. Looking forward to my next visit.

The jury is still out on the fossil – stay tuned.

Ah yes, the infamous “camping” trip to the coast in Feb. ’73. Details remain hazy nearly 40 yrs. later but I’ll never forget that night on the porch and waking up in the morning covered in snow:) Come to think of it that’s not the only “spring” trip we took that exposed us to Mother Nature’s unpredictable side: Lake Santeetlah, anyone? Let’s hope May in the Smokies plays nicer. Great post, Bob.

The extremes of nature are predictable too, yes? More storms in the future? Interesting the purpose they serve, i.e. contributing to migration of barrier islands.

I’ll work in the Lake Santeetlah story in the near future when I get that next shock of cold water. Not planning on it when I sail tomorrow (if the winds blow).

Great post, Dad. It really does make us appreciate what we have to reflect on these memories. Even at the age of 6, I still have memories of Hugo in ’89. I’m also glad you’re not pushing yourself and Kingfisher in larger waves and stronger winds these days!

Sara, one of the most important lessons I learned with Hugo is that you have to get out of the way of these storms. Evacuating with you, Eliot, and your Mom was one of the most important decisions I have made in my life.