My recent forays into Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge have been high tide ventures to observe the American Oystercatcher roosts on shell rakes along the Intracoastal Waterway. On this Monday, I chose an opposite course, exploring the low tide waterways to view foraging oystercatchers. I planned to enter a very shallow area a little to the south of Garrison Landing called Sewee Bay, another example of misnaming. The original Sewee Bay, a shallow seven-mile opening to the Atlantic Ocean between Bull Island and the northern Cape Romain islands, is now known as Bulls Bay.

I have sailed around the periphery of Sewee Bay, but never ventured far in Kingfisher, my Sunfish class sailboat, always finding the bottom with daggerboard or rudder. But my kayak would allow access to very shallow water, mud flats, and oyster banks, prime foraging grounds of oystercatchers. No charts of these waters existed, except probably in the minds of oystermen and oystercatchers. So I penciled a crude chart taken off a Google Earth image, and paddled south toward my entry point.

The access was shallower than I imagined, even with at least one and a half hours before low tide. I gamely paddled on, sliding through inches of water and along the muddy bottom, searching for the slightest channel. I paddled deeper into the disappearing water. Soon I was paddling more on mud than water, and had reached a point of no return. Efforts to break loose and find a little water were in vain. Time was of essence now, with a strong possibility of running out of water completely and spending the next 3-4 hours waiting for the incoming tide to free me. I dismissed the thought of getting out to pull the kayak along, realizing I would sink deeply into the pluff mud.

Deeper water was clearly fifty yards ahead, but how to get there? Pulling deeply with the paddle into the mud only gained inches. I added to the inches by using body movement – “ooching” – to will the craft forward a little more. I slowly angled the craft toward the bank where perhaps a little slough might prove an escape route. I’m sure my course was marked by a groove in the mud astern but it was no time to take a photo. I found a little bit of water, and slowly made more progress. A long exposed mud bank was ahead with white poles standing up, leaving a narrow channel parallel to the marsh – it was my release to deeper waters.

Avoiding a muddy fate, I stuck to waterways to explore. An occasional oysterman worked on the banks for the harvest. Shorebirds foraged, dowitchers plunging their bills deeply in the mud for invertebrates.

Oystercatchers also foraged along these same banks. I followed two, drifting along near them. They walked along the bank, giving me plenty of time to photograph, and just watch. The oystercatcher’s bill is so prominent – all field mark. On closer examination their eyes are similarly distinctive: a bright red outer ring, a yellow inner ring, and a dark center – in sum a celestial jewel.

I considered a different route to make my way back to the landing, but finally returned to the ICW. The tide had fallen further, and a waterway I had earlier come through was completely blocked by an exposed oyster reef. An osprey flew past, also heading north, and made a rapid diagonal descent, hitting the water with a crash and bringing up a fish. It worked to gain altitude, adjusting its catch in its talons, and passed again heading in the opposite direction, its actions facilitating my viewing.

Arriving at the landing for a take out, the basin before the ramp was mainly exposed mud, with only a little narrow channel that resisted my effort to push through. During the wait, I went for a paddle, and then returned to chat with a neighbor on the dock, willing the tide in.

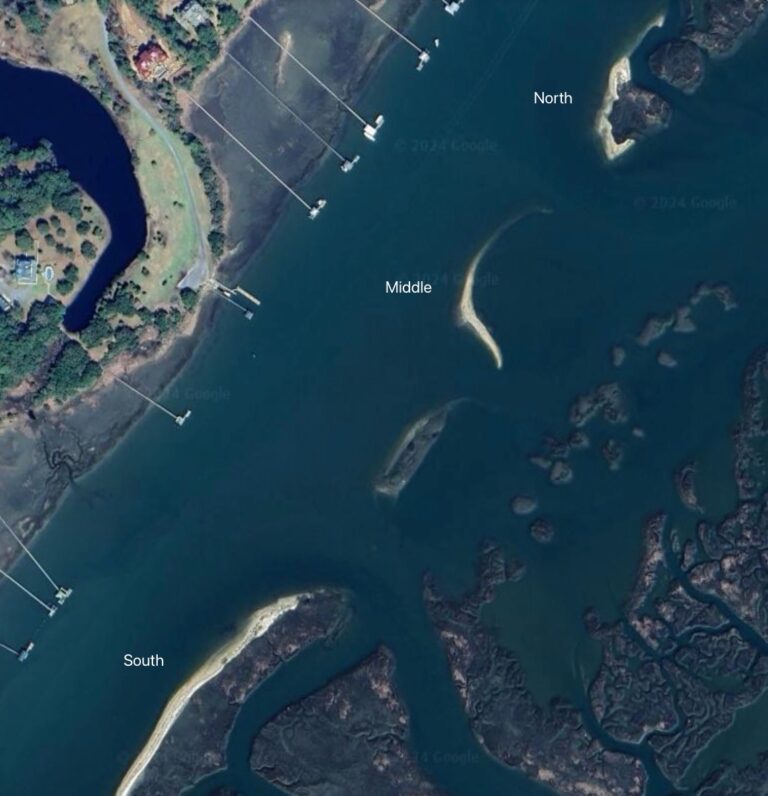

On Thursday, I was back at the landing, my portal to the immense world of Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, for another kayak venture but on an opposite tide. A quick microgeographic orientation. The closest shell bank has the lowest elevation, and is covered by many high tides. The other two shell rakes where the oystercatchers gather for their diurnal high tide roosts are to the north and south of the landing. So for nomenclature, I will refer to the north shell bank, the middle shell bank, and the south shell bank. (See below map from Google Earth, probably at low tide).

Looking out to the middle shell bank, perhaps a dozen oystercatchers along with one brown pelican were standing on the slowly disappearing land. As I prepared to launch, a cabin cruiser passed by heading north, the small waves of its wake breaking on that bank and scattering almost all the birds except one oystercatcher and the pelican. The flushed birds flew and landed on the north shell bank to join a large contingent of the flock. Paddling toward them across the ICW, the two holdouts took off and followed the others to land on the northern roost, my destination for photography and observation.

With the late morning light, I sought the back side of the shell rake, gently paddling in to the marsh grass for “mooring” the kayak. My presence accepted by the flock, I took photos, then moved to the other side of this little creek into the marsh. Towering over the oystercatcher gathering was the brown pelican, a ghostly presence. Putting down the camera, I just took in the scene.

Leaving that place, I paddled off to find a small waterway to connect with Anderson Creek, using the flooding tide to cross areas not usually accessible. The kayak knifed through a narrow section of marsh grass, recalling days on the North Carolina coast sailing through flooded marshes and parting the cordgrass. I finally found the sought waterway for the passage to the larger creek. Making the turn back toward the mainland, a flight of birds appeared in the distance, turning and heading south, surely part of the oystercatcher flock. I chose an alternative course to the south to inspect the southern shell bank.

Coming around to the ICW, and turning north, I viewed this bank and birds roosting along it. Passing by the birds, I recalled a similar course on a calm day where I heard the sound of toes clacking over the oyster pile. Questions continued to spill out about this flock, and oystercatchers in general. In communication with Judy Drew Fairchild from Dewees, a kindred spirit, I learned she had been observing the flock, and reporting her resightings of banded birds to the AMOY working group for almost a decade. She was certainly a “follower”, and after a recent photography session Judy realized there were over fifty banded birds from those images. (Judy, by the way, has a fine web, Nature Walks with Judy, containing excellent one-minute nature videos). The AMOY working group has many members, professional and lay, and a mission to support research and management efforts to promote conservation of the American Oystercatcher. This organization even has an annual meeting: these birds have quite a following.

I decided to paddle back to the north bank and view the flock. Drawn to this high tide roosting phenomenon, I had embraced the role of oystercatcher follower. I had entered another portal through the AMOY working group web where all the resightings of a bird I had reported were listed: its banding on Long Island, annual returns to that site, and several winter ones in Cape Romain, before my report a few weeks ago. All this information generated more questions, and an abundance of wonder. A realization emerged that this flock had been here all the years of my Awendaw residence of over forty years, surely in plain sight, but only now entering my awareness. Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge plays a vital role in the conservation of this species.

Again approaching from the back side, I noted that the gathering was perhaps half the size of earlier. Taking leave to return to the landing, a flock of birds in flight appeared to the south. In two groups they headed north a few feet above the water, joining the birds on the northern shell bank. In recalling this flight later, another question surfaced – who was following who?

I became a follower both on the water and on land. From the mainland and docks with binoculars I was able to keep track of the high tide roosts on the shell rakes, and found myself drawn to those views. Christmas week I watched the flock arrayed on the north bank hunkered down in a strong northeast wind. (The flock on the roost are often good wind indicators, their beaks pointing toward the flow.) The following day the northern bank was empty two hours before the high tide. Watching from the landing, the middle bank had twenty oystercatchers. The flock appeared to the south, gathered in flight heading to the north bank. They turned and landed. I waited for the middle bank birds to join them, but instead another large group appeared from the south, and circled the north bank, turning and flying back to land on the southern bank. Then the remaining contingent on the northern bank took off and joined the southern bankers. Questions, questions: What was going on? What role does socialization play in the AMOY flock? After foraging, how does the flock gather, and are there leaders that direct the joined flock back to the high tide roosts? On these crowded shell banks how do the birds find their positions, particularly when joining a settled group? Questions to ponder.

Bob, I love this! We are kindred spirits indeed! I find that everytime I go out, there are more questions and mysteries to solve! Happy Holidays!

Those mysteries contribute to the awe experience. But if you have any answers to my posed questions, feel free to pass them on.

Hey Judy, a blast from the past here … Bonny Luthy, friends and a neighbor of Bob. Trust that you and your family are well and had a Joy-filled Christmas! All the best for a safe, healthy and blessed New Year!

Thanks for sharing! I love the line about the flock being there in plain sight, but only now entering my awareness. That line relates to so many things in our life and how we should focus on being more mindful (may have to use that line with my patients!)

Please do use that line. Being more mindful is a good resolution for 2025, hey?

Thank you,Bob. You are such a great writer and I so appreciate you sharing your adventures and photos of this beautiful place we feel so fortunate to live!

Thanks Bonny

Hi Bob, thanks for introducing me to this beautiful bird. Are they crafty enough to ever catch the elusive oyster though?

Oh they do Mike. At low tide they walk around until they find one with the bivalve shell opened up, and use that incredible bill to cut the adductor muscle to fully open the shells for eating.

They are well equipped and aptly named. I needed one at an oyster roast yesterday. Happy New Year to you & Susan!

Best wishes to you and the growing family!

Hey neighbor, enjoyed reading this. Rob and I would love to tag along on a kayak adventure sometime!

Yes, let’s plan that kayak adventure for 2025.

I really loved reading about this adventure, Bob- thank you! I have been taking occasional bird walks with Charleston County Parks on Folly, where Keith McCullough teaches about Oystercatchers. Your line about the boat flushing them out reminded me of the constant pressure these birds are under. Thank you for “taking me with you” to support them.

Hey Sara, if you are entering the bird world, and haven’t got it, you will love Amy Tan’s The Backyard Bird Chronicles. Also to explore more about oystercatchers, go to the AMOY working group website I linked in the post.

Wonderful to see these beautiful birds up close. Interesting they go back to Long Island. I’d like to make that migration regularly. Thank you for sharing. You help to keep us in awe! Dana

They are migrating to a number of states on the East and Gulf Coasts. Happy to share the awe

Really enjoyed this read Bob and glad to see you continue to learn, grow and share your vast knowledge and observation skills in nature with others. Felt like I was along for the ride and now I have a new bird to learn more about too! Thanks as always!

Thank you Julia. If you want to learn a lot more about oystercatchers, following that link to the AMOY working group